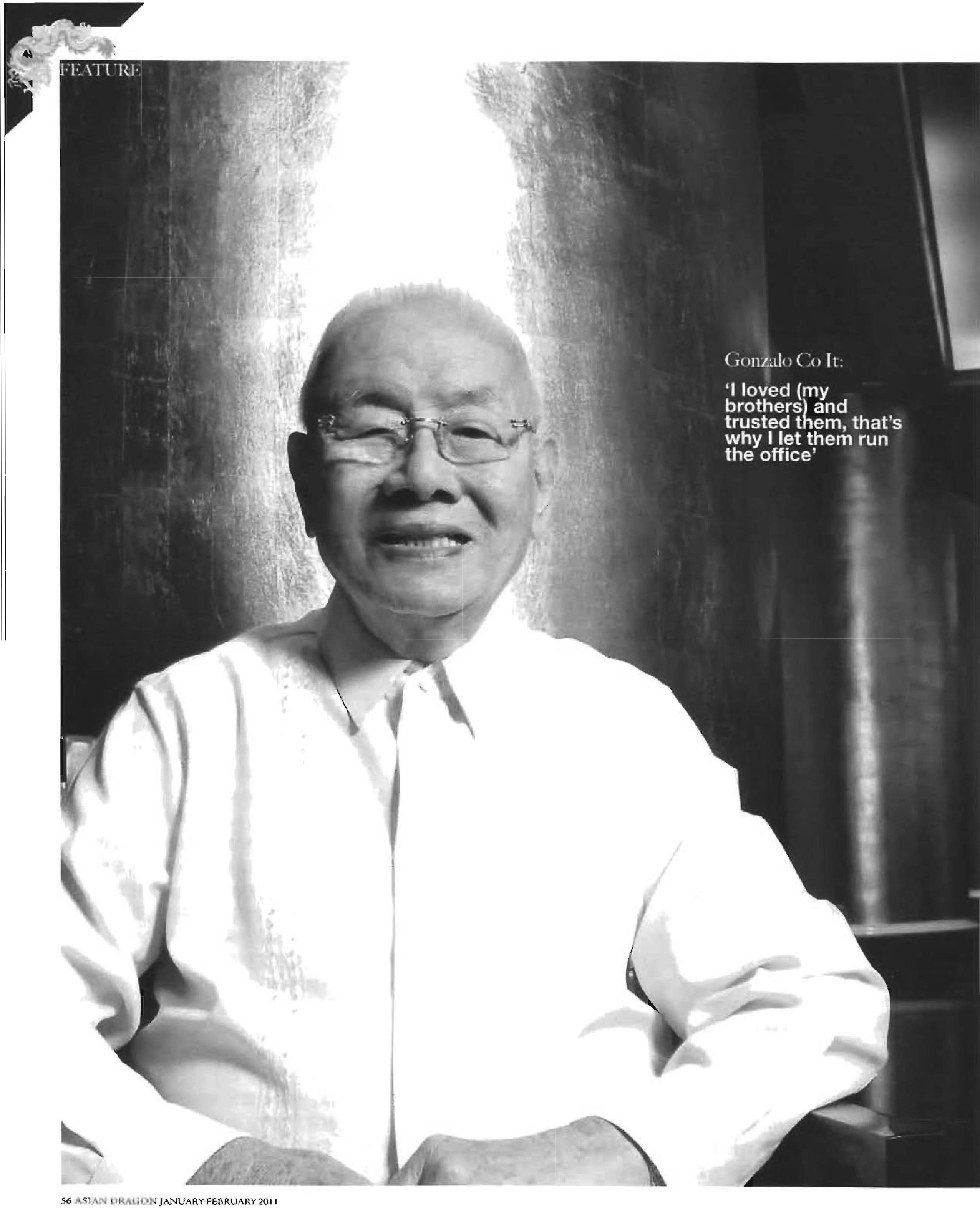

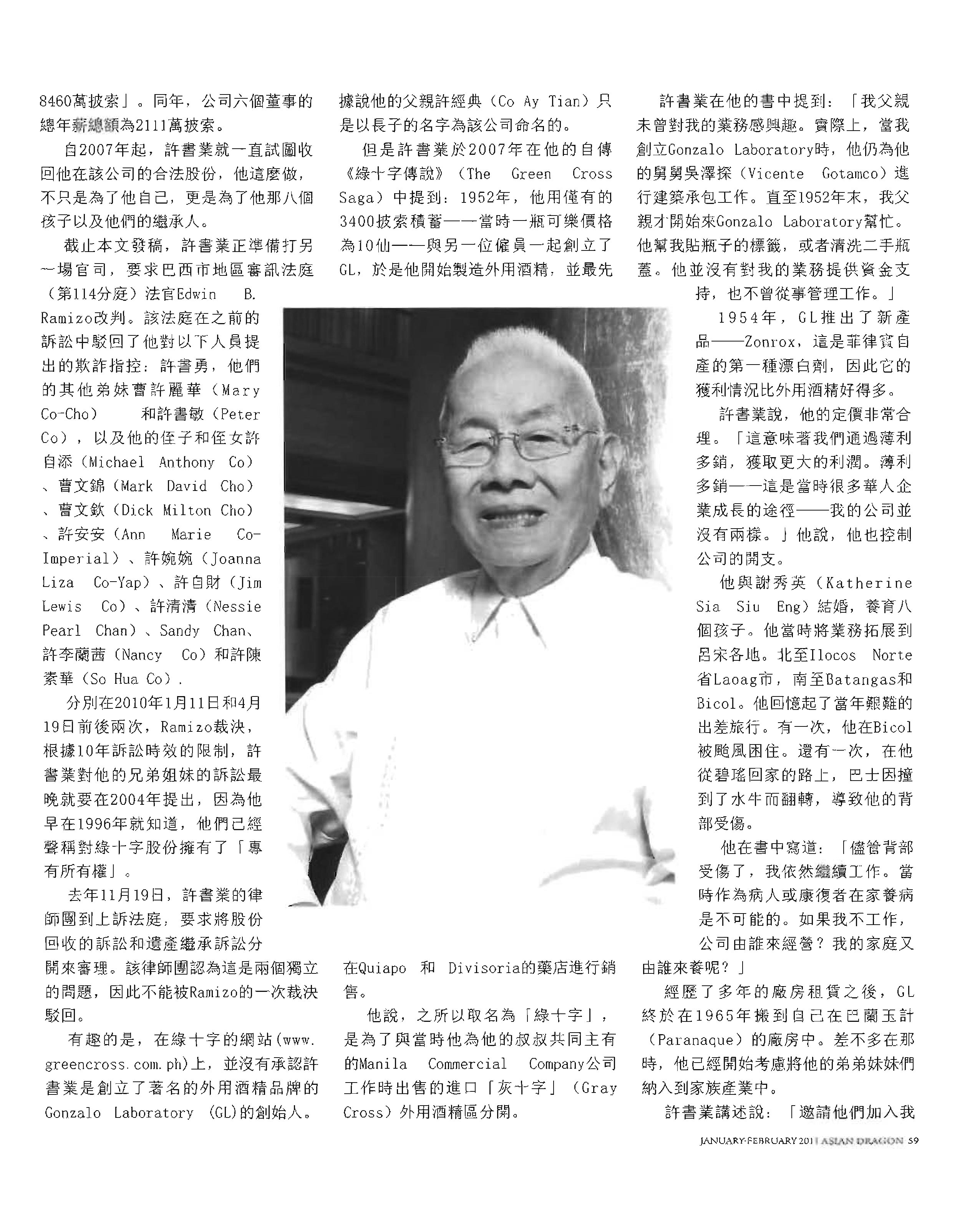

Gonzalo Co It once had it all materially. Now, at 91, he has only the love of his children and grandchildren, whom he feels he has let down. Peace eludes him as he continues to be dogged by what he claims was a mistake that changed his fortune and those of his children.

He says his love and concern for his younger siblings made him leave in their hands the company he founded, Green Cross (originally Gonzalo Laboratories), maker of popular consumer products Green Cross Rubbing Alcohol and Zonrox Bleach. Now run by his youngest brother Anthony, Green Cross is a multi-billion-peso conglomerate, having expanded its product lines to include soaps, an all-purpose cleaner and fabric softener, colognes, and face powder.

Securities and Exchange Commission records show that in April 2010, the company’s “unrestricted/unappropriated retained earnings as of end of last fiscal year (2009) was P288.46 million.” Its six board directors received a total annual compensation of P21.11 million that same year.

Since 2007, Gonzalo has been trying to reclaim what he says is his rightful share in company, not just for himself, but for his eight children and their heirs.

As of this writing, Gonzalo was gearing up for yet another legal battle to reverse the decision of Judge Edwin B. Ramizo of the Pasay City Regional Trial Court (Branch 114) to dismiss the estafa case he filed against Anthony, and their other siblings, Mary Co-Cho and Peter Co, as well as nephews and nieces Michael Anthony Co, Mark David Cho, Dick Milton Cho, Ann Marie Co-Imperial, Joanna Liza Co-Yap, Jim Lewis Co, Nessie Pearl Chan, Sandy Chan, Nancy Co, and So Hua Co.

Twice this year, on January 11 and again on April 19, Ramizo ruled, under the 10-year Statute of Limitations, Gonzalo only had until 2004 to file his case against his siblings, because he knew that they had claimed “exclusive ownership” of Green Cross shares as early as 1996.

Last November 19, Gonzalo’s lawyers went before the Court of Appeals, asking it to separate the Complaint on the Reconveyance of Shares from an inheritance case, which Gonzalo’s lawyers believe are two separate issues, and thus shouldn’t have been dismissed with just one decision by Ramizo.

It is interesting to note that in the website of Green Cross (www.greencross.com.ph). Gonzalo isn’t acknowledged as the founder of Gonzalo Laboratory (GL), which created the popular rubbing alcohol brand. His father, Co Ay Tian, was said to have just named the firm after his eldest son.

But as Gonzalo tells in his 2007 autobiography The Green Cross Saga, in 1952 he used his savings of P3,400 — a bottle of Coke then cost 10 centavos — to set up GL, and with just one other employee, he made the rubbing alcohol and sold it initially to drugstores in Quiapo and Divisoria.

He says he named it Green Cross to distinguish it from Gray Cross, the imported rubbing alcohol he had earlier sold when he was still working for the Manila Commercial Company, a firm his uncle co-owned.

“My father never had an interest in my business. In fact, while I established Gonzalo Laboratory, he continued working as a building contractor for his uncle Vicente Gotamco. It was only in the latter part of 1952 that my father started coming to Gonzalo Laboratory. He would help out, sticking labels on the bottles or washing secondhand bottle caps. He did not infuse any capital into my business, nor did he manage it,” Gonzalo pointed out in his book.

In 1954, GL introduced a new product, Zonrox, the first bleaching agent made in the Philippines, which made more money than the rubbing alcohol.

Gonzalo says he kept their prices reasonable. “That meant our margins stayed slim, and the only way we could earn more was to increase the volume of sales. Pera-pera ang kita, pero marami benta — this was how many Chinese enterprises of that era grew — and mine was no different.” He says he also controlled the company’s expenses.

Married to the former Katherine Sia Siu Eng and with eight kids to feed, he branched out all over Luzon, from Laoag, Ilocos Norte, in the north to Batangas and Bicol in the south. He recalled how difficult traveling was at that time. Once he was stranded by typhoon in Bicol. Another time on his way home from Baguio, he hurt his back when his bus flipped after hitting a carabao.

“Despite my back injury, I continued working. At that time, staying at home as an invalid or as a recuperating patient was not an option. If I didn’t work, who would run the company and feed our families?” he wrote in his book.

In 1965, after years of renting, GL transferred to its own building in Parañaque. It was also around this time that he began taking in his siblings into the family business.

“By inviting them to join me, I was fulfilling (a Chinese custom) my obligation as the eldest brother, to take care of my younger siblings,” Gonzalo narrates. “Because I loved them, I trusted them and let them have the run of the office, while I concentrated on marketing and sales, which I was good at. This meant that I was out a lot, opening new markets for our products.”

Then he says, in 1971, his brother Joseph persuaded him to convert the company into a corporation. Gonzalo says he agreed because he didn’t want to offend Joseph. On August 11 of that year, GL became Gonzalo Laboratories Inc. and was registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission with an authorized capital of P500,000, of which P200,000 worth of shares or 2,000 shares were subscribed to. Each share had a par value of P100.

Of the 2,000 shares, 1,000 went to Gonzalo, 400 to his brother Anthony, and 200 each to their mother Ang Si and siblings Joseph and Mary. Only Gonzalo and Anthony were Filipino citizens; the other incorporators were listed as Chinese nationals.

Of the authorized capital, P70,000 was fully paid up, with Gonzalo paying for P67,000 of his subscribed shares in the company. This was followed by P1,500 from Anthony, while their mother, and siblings Joseph and Mary supposedly paid P500 each for their shares. But according to Gonzalo, he was the only one who put money into the new corporation, as his other Siblings didn’t have the money. Gonzalo claims he gave these shares to his siblings only “by implied trust,” and could demand return of the shares when he wanted to.

He adds that it was only years later that he discovered that his shares had devalued because the number of shares was increased. As per the amended articles of incorporation adopted on December 29, 1986 and approved by the SEC in 1988, GLI’s authorized capital was increased to P2.5 million “divided into 25,000 shares” with a par value of P100 each. The same document showed Gonzalo’s signature, however, signifying his approval.

The document was also Signed by his father Co Ay Tian as a board director of GLI, as by then, his wife and Gonzalo’s mother, Ang Si, had passed away. Other signatories to the Directors’ Certificate adopting the amended articles of incorporation were Joseph, Anthony, and another sibling, Peter, who was board secretary. By 1996, a new certificate showed that Gonzalo had only 100 shares to his name.

In a recent interview with Asian Dragon, Gonzalo and his children say that things came to a head in 1986 when Joseph, who was then running the company, had an argument with Syril, Gonzalo’s eldest son, over a business opportunity. “He (Joseph) told me, ‘Either you get out from the company or I get out.’ And I said, ‘I’ll get out,'” Gonzalo recalls. Joseph reportedly paid him P9 million for his 17.5 percent share in the firm. “But the money came from the coffers of my own company. It was me paying myself, so how could that be a sale?” Gonzalo notes in his book. Still, he was retained as chairman of the board with a salary equal to that of Anthony, who was named president.

Asked why he agreed to leave the firm, his daughter, Ana Kho Puno, pipes in, “Because my father loved him (Joseph) so much. My father doesn’t like to quarrel. It’s his being Chinese. The huge gap in their ages made it so that his thinking was, they were like his own children. We felt that he loved them as much as he loved us. He was willing to give up everything to them.” By leaving the firm, however, Gonzalo’s children also lost their link to the company.

Marciano suspects that “Joseph feared we, Gonzalo’s children, would take over the company. There was a big age gap between Gonzalo and Joseph, the latter being just a few years older than Gonzalo’s eldest, Syril.

By May 23, 1991, as per court documents, GLI had already been incorporated as Green Cross Inc., and the general information sheet filed with the SEC showed just one share in Gonzalo’s name.

Meanwhile, Joseph passed away in 1992 from a heart attack while traveling in Hong Kong.

Gonzalo says he decided to finally reclaim his shares in the company because in July 2006, he dreamt that his wife Katherine, who died in 1983 from cancer of the pharynx, told him “to get what was mine for the sake of the children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren.” He claims he left the company “under duress.” His children Marciano and Ana say that if their mother had still been alive, she would not have allowed Gonzalo to leave the firm.

Gonzalo asked Judge Ramizo’s court to order each of his siblings to return to him 333.7 shares in Green Cross, as well as “any cash, stock, or property dividends he had earned on these shares, pay him P1 million as moral damages, P1 million as exemplary damages, P500,000 as attorney’s fees and litigation expenses, and also pay the costs of the suit.” He lost.

Gonzalo then filed for a motion for reconsideration on January 28, 2010. In opposing the motion, Anthony’s family pointed out that Gonzalo signed several documents approving the increase in shares of Green Cross, leaving him with only 100 shares amounting to P100. “His signature on the ‘certificate’ to increase the capital stock confirms” that Gonzalo knew their parents were no longer stockholders of the company and their shares were “now owned, possessed, and registered in the name of the defendants.”

Anthony’s lawyers said Gonzalo had not shown any documentary proof to contradict the certificate. They also said the Pasay, Manila, and Parañaque courts “have dismissed all eight” estafa complaints.

Gonzalo is now asking the Court of Appeals (CA) to separate the issues of asking his siblings to return his rightful shares to the company, and the estate proceedings of their parents’ assets.

According to Gonzalo’s personal lawyer, Fiorello Jose, there was no clear transfer of assets to Gonzalo and his siblings from their parents — Ang Si (mother) and Co Ay Tian (father) — when they passed away. As such, no document exists proving that Gonzalo had turned over whatever he had inherited from his parents, to his siblings, in this case, supposedly the shares to the company. So Gonzalo is asking the CA that a separate probate court be assigned to preside over the estate proceedings of their parents.

Gonzalo lives in an old, decrepit house in Pasay City, but is hopeful that he would still be reconciled with his siblings,” and I trust that God will do it in my lifetime.” AD